September 11, 2015

jerem.

When geometry is taught in school, it focuses on the rules that defines simple forms like squares, triangles or other shapes that can be drawn on a sheet of paper, or solids that can be represented in 3D.

All these definitions are based on a set of base rules (axioms) identified by Euclid around 300BC. Over the past millennia, the study of geometry has been extended a lot and the word is no longer limited to the study of shapes and solids in 2 or 3 dimensions.

One important step toward this generalisation was made by carefully inspecting Euclid's axioms and investigating what happens when some of them are omitted. As an illustration, I want to give an example of what happens when one ditches Euclid's fifth axiom which can be stated as follows:

If one takes one straight line and a point outside of that line, there is only one line that is parallel to the other and passes through the point.

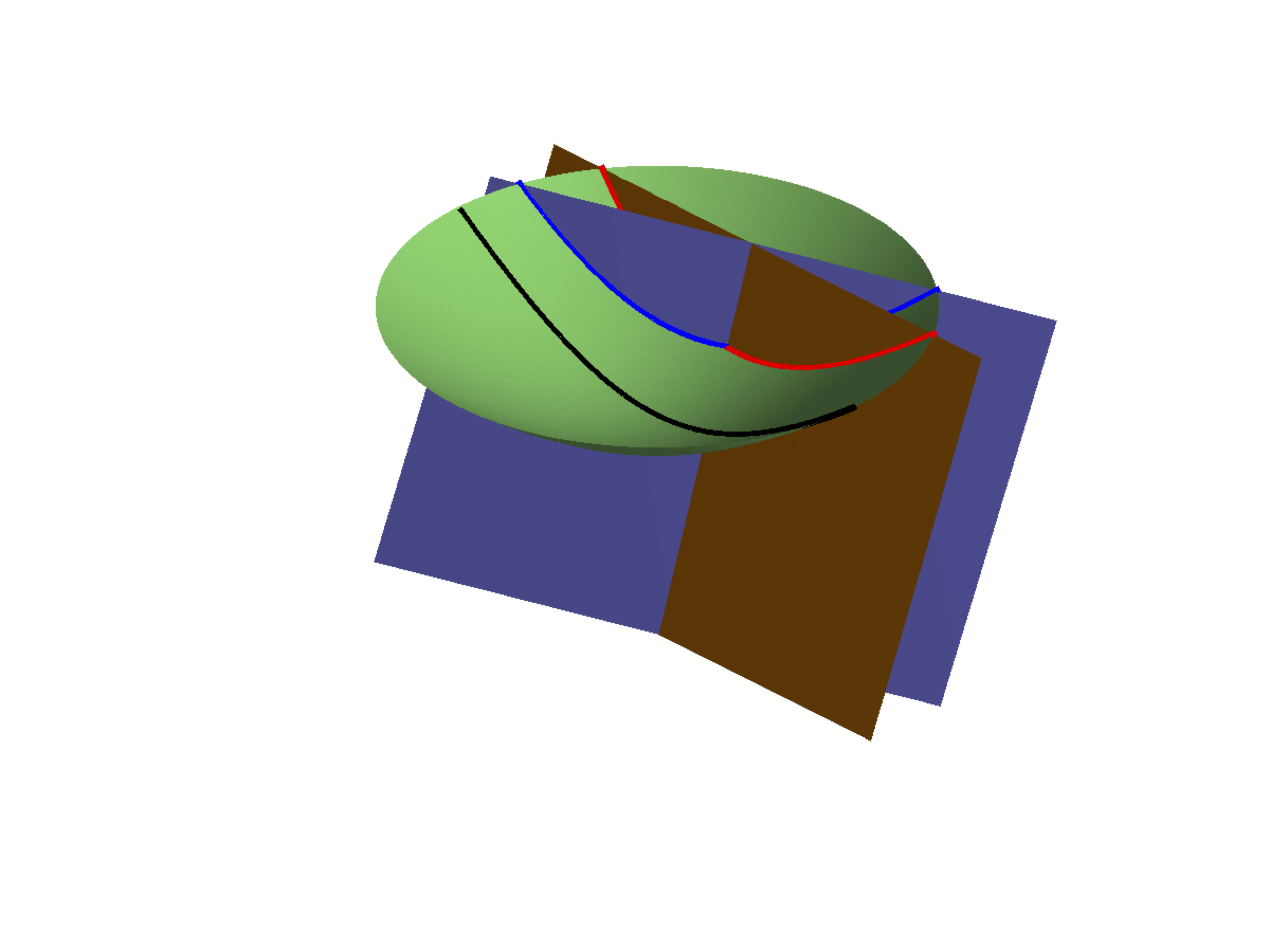

The above expression feels very natural as we are used to dealing with straight lines on black boards and flat sheets of paper. But there are important cases where Euclid's fifth is not applicable. Take, for example, the case of the (two-sheet) hyperboloid which corresponds to the green shape on the picture below.

The first difficulty lies in the meaning to attribute to the concept of a straight line on such surface. One way to define these straight lines that is mathematically perfectly valid, is to identify them as the result of the intersection of the hyperboloid and planes that pass through the origin of coordinates (see illustration). In order to avoid confusion, mathematicians prefer to denotes such curves as geodesics and to keep the term 'straight line' for flat space. There are three different geodesics represented on the above picture corresponding to the black, blue and red curves.

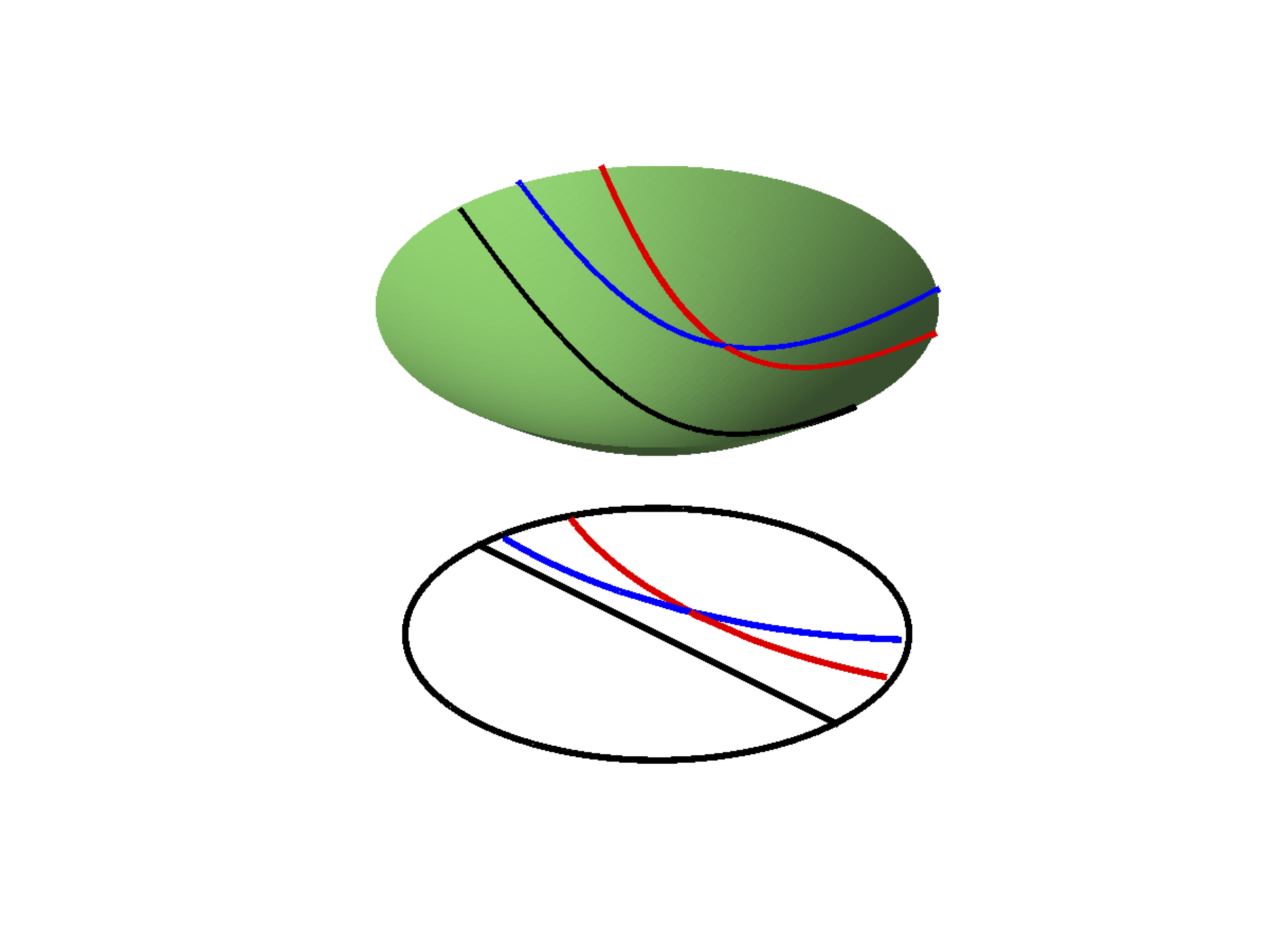

Now, even though the blue and red lines intersect in one point, neither of these intersect the black line and thus both can be considered as parallel to it. One could argue that this might be true of the hyperboloid of the figure, which is limited in space, but not of the whole infinite hyperboloid surface. In fact, it is true even in that case and this can be verified by looking at a representation of the hyperbolic space due to Poincaré. This representation maps all the points of the infinite hyperboloid to points within the disk of unit radius as illustrated on the picture below.

In this picture, the black circle represents the set of points situated at an infinite distance to the centre of the hyperboloid (the lowermost part of the surface). As we can see, the red curve and the blue curve both reach infinity without ever crossing the black geodesic, contrary to the prescription of the fifth axiom. The choice of the blue and red geodesics was made arbitrarily. There is nothing particular about those two curves and the argument presented above remains valid for all pairs of curves that intersect at a point. The conclusion is that, on the surface of the hyperboloid, there are an infinity of geodesics parallel to another that passes through the same point.

The algebraic expression of the Poincaré map is fairly simple in terms of polar coordinates:

$$

\{r,\theta\}\rightarrow \left\{\frac{r}{1+\sqrt{1+r^2}},\theta\right\}~.

$$

Geometrically, this corresponds to the intersection of the line joining a point on the hyperboloid with the point of coordinates $(0,0,-1)$ and the plane that satisfies $z=0$. This is an example of a stereographic projection. One sees that this transformation maps the entire hyperboloid to a finite disk by considering the following limit :

$$

\lim\limits_{r \to \infty}\frac{r}{1+\sqrt{1+r^2}}=1

$$

Non-euclidian geometry is a very useful topic of mathematics and has many applications, notably in physics. One of the most important is in General Relativity in which space-time is a non-euclidian 4D space and its curvature is identified with gravitation.