June 12, 2016

jerem.

This post is something I have been meaning to share for a while.

One day I had carried my meal to work in a lousy box which I kept closed with two rubber bands. I started playing with the rubber bands and noticed that, when I want tried to fit in one within the contour of the other, the following happened.

I wondered if there were a mathematical explanation why the inner band would always have this inward pointing bulge. In this post, I am going to present a geometrical description of the phenomenon.

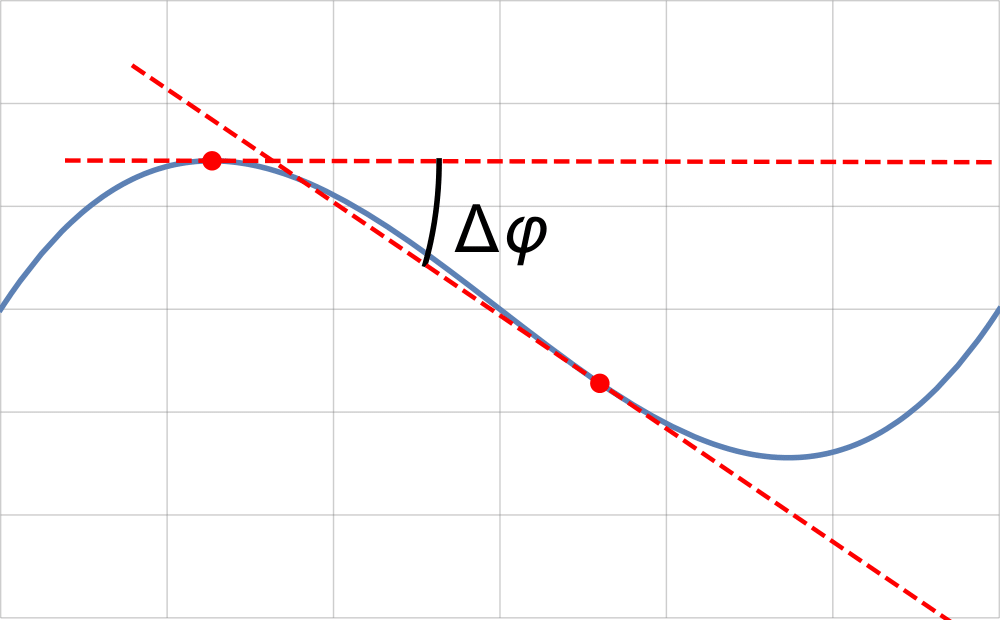

In the language of differential geometry, the inner rubber band experiences a change in its local curvature along its contour. The curvature can be defined as the instantaneous change in the angle made by the tangent vector to the curve and some arbitrary axis (see figure below) :

The formal definition is

$$

k(s)=\frac{d\phi}{ds}~,\label{eq:k(s)phi}

$$

where $s$ is a continuous real parameter varying continuously along the curve. $k(t)$ is a signed quantity whose sign change with the concavity of the curve :

An intuitive way to understand the above definition is to look at that the angle $\Delta\phi$ spanning a small element of curve that we identify as an arc of length $\Delta s$. Imagine then that this arc is part of a circle tangent to the curve at the point of interest. By definition that circle has a radius, $R(s)$, which satisfies

$$

\frac{1}{R(s)}=\lim_{\Delta s\rightarrow 0}\frac{\Delta\phi}{\Delta s}=\frac{d\phi}{ds}~.

$$

The curvature at a point is then the inverse of the radius of curvature of the imaginary circle tangent to the curve at this point.

The advantage of the above definition is make apparent a very elegant result. The integral of the curvature along a closed curve (the total curvature) is

$$

\oint_\mathcal{\gamma} k(s)ds=\oint_\mathcal{\gamma}\frac{d\phi}{ds}ds=n~2\pi~,

$$

where $n$ is an integer counting the number of times the curve winds around itself called the winding number.

I now want to verify the above result in some special cases. Eq. \eqref{eq:k(s)phi} is not ideal for that purpose. In order to find a substitute, we start from a more general way to parametrise any curve.

Let a curve $\gamma$ be parametrised in 3d space using cartesian coordinates as

$$

\vec{\mathcal{\gamma}}^T=(\gamma^x(\lambda),\gamma^y(\lambda),\gamma^z(\lambda))~,

$$

where $\lambda$ denotes any affine parameter that varies continuously and monotonously along the curve. Then the length element of $\gamma$ is

$$

ds=|\vec{\mathcal{\gamma}}(\lambda)|d\lambda~.

$$

Hence the total length of the curve is

$$

S=\oint_\mathcal{\gamma}ds=\oint_\mathcal{\gamma}|\vec{\mathcal{\gamma}}(\lambda)|d\lambda~.

$$

In this parametrisation, the expression for the curvature changes to

$$

k(\lambda)=\frac{1}{|\vec{\mathcal{\gamma}}(\lambda)|}\frac{d\phi}{d\lambda}~.

$$

This new expression does not alter the formula for the total curvature:

$$

\oint_\mathcal{\gamma} k(s)ds=\int_\mathcal{\gamma}\frac{d\phi}{ds}ds=\int_\mathcal{\gamma}\frac{d\phi}{d\lambda}d\lambda~,

$$

Focusing on curves in 2d, we have $\vec{\mathcal{\gamma}}(\lambda)^T=(x(\lambda),y(\lambda))$. Wecan chose the angle $\phi$ via the following :

$$

\frac{x'(\lambda)}{\sqrt{x^{\prime 2}+y^{\prime 2}}}=\cos\phi

$$

$$

\frac{y'(\lambda)}{\sqrt{x^{\prime 2}+y^{\prime 2}}}=\sin\phi~.

$$

Then,

$$

\frac{d}{d\lambda}\frac{y'(\lambda)}{\sqrt{x^{\prime 2}+y^{\prime 2}}}=\cos\phi\frac{d\phi}{d\lambda}=k(\lambda)|\vec{\mathcal{\gamma}}(\lambda)|\cos\phi=k(\lambda)x'(\lambda)~,

$$

so that

$$

k(\lambda)=\frac{y'' x'-y'x''}{(x^{\prime 2}+y^{\prime 2})^{3/2}}~.\label{eq:klambda}

$$

This is the more practical expression for the curvature that we were looking for. We are now ready to look at a few examples.

A circle

We choose $\lambda\equiv\theta$, the polar angle : $\vec{\mathcal{\gamma}}(\theta)^T=(r\cos\theta,r\sin\theta)$. The curvature is a constant and so is the curvature radius, which is simply the radius of the circle :

$$

k(\theta)=\frac{1}{r}~,

$$

and its integral gives

$$

\int_0^{2\pi}\frac{1}{r}~r~d\theta=2\pi~.

$$

An ellipse

We can parametrise the ellipsoid as : $\vec{\mathcal{\gamma}}(\theta)^T=(a\cos\theta,b\sin\theta)$, then:

$$

k(\theta)=\frac{ab}{(b^2\cos^2\theta+a^2\sin^2\theta)}~,

$$

which, indeed, integrates to $2\pi$ for all $a$ and $b$.

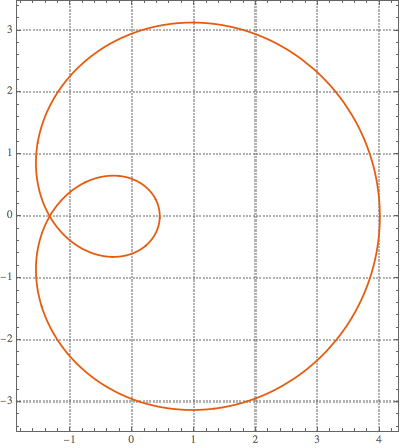

The Nyquist curve

This example is a bit more complex. The curve winds twice on itself and is parametrised as $\vec{\mathcal{\gamma}}(t)^T=(\text{Re}[\frac{1}{(-\frac{1}{2}+e^{it})^2}],-\text{Im}[\frac{1}{(-\frac{1}{2}+e^{it})^2}])$ and its curvature is

$$

k(t)=-\frac{1}{16} (5-4 \cos (t))^2 (2 \cos (t)-7) \sqrt{-\frac{1}{(4 \cos

(t)-5)^3}}~.

$$

Using this, the total curvature can be computed to be :

$$

\int_0^{2\pi}k(t)dt=4\pi~,

$$

as expected for a curve with a winding number $n=2$.

Now that we have convinced ourselves of the validity of Eq. \eqref{eq:klambda}, we can understand the reason behind the bulge in the inner rubber band of the first figure.

As the inner rubber band is forced within the contour of the other, its curvature must be bigger on a large portion of the curve (more positive). However, as the total curvature must remain equal to $2\pi$, there must be a region of negative curvature to compensate. Hence the bulge.

Incidentally, there is a way of getting one rubber band inside another without the bulge, you just need to increase the winding number: